In 1999, I was a teenager who spent far too much time glued to a screen, thumbs calloused from hours of International Superstar Soccer—the game that would eventually evolve into the cult classic Pro Evolution Soccer. Among the many quirks that made it special, there was one feature that held me in a romantic kind of awe: the all-star teams. Europe XI versus the Rest of the World XI.

Konami's version

It wasn’t just a gimmick—it was a playground for imagination. The idea of assembling a team made up of the greatest players from each continent and setting them against one another felt mythological, like something out of a footballer’s folklore.

South America, I always thought, could stand toe-to-toe with Europe. Possibly even beat them. But Konami decided to balance the scales by calling on Asia, Africa and North America too. No Oceania though. Mark Viduka didn’t make the cut—you’ll soon see why.

On the digital pitch of Europe’s XI, there was Angelo Peruzzi in goal. In front of him stood a terrifying back three of Marcel Desailly, Fernando Hierro, and Jaap Stam—hard men all. Edgar Davids held down midfield with his trademark ferocity, Raúl and Beckham roamed the flanks, and Zidane pulled the strings in the middle. Up front, Anelka drifted in from the left, Shevchenko from the right, and in the middle: golden goal hero Oliver Bierhoff.

The Rest of the World XI, by contrast, felt madder. Looser. More unpredictable. In goal: the legendary firebrand José Luis Chilavert. The back line featured Taribo West and Roberto Ayala, with Roberto Carlos and César Arce running the flanks (yes, Cafu was on the bench). Fernando Redondo, as elegant as he was combative, sat in front of the defence. Then came the chaos: Rivaldo, Mustapha Hadji, and Álvaro Recoba.

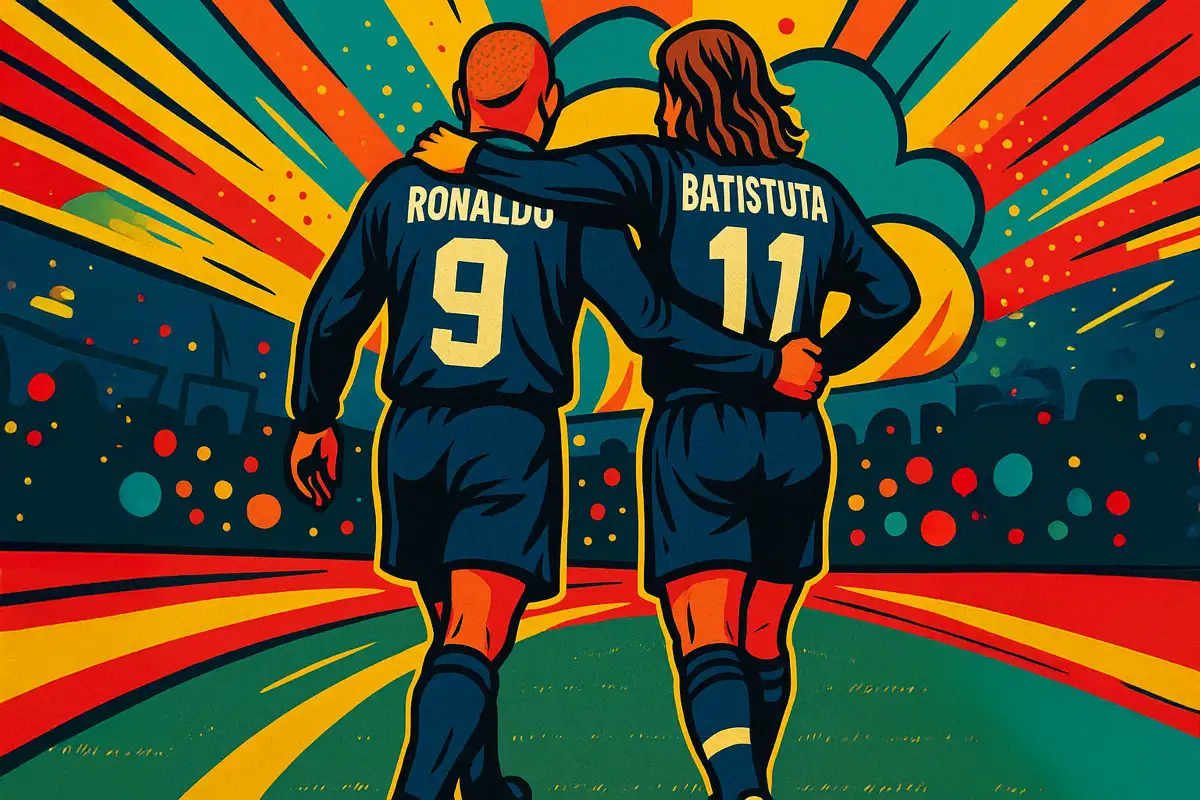

But up front… up front there was something divine. A strike partnership written in the stars and programmed into plastic discs: Ronaldo and Gabriel Batistuta.

Even in the artificial world of the PlayStation, it felt perfect.

But Did It Ever Happen?

Now a father, my children laugh when they see the polygon faces and jagged edges of my old games. But something recently stirred in me. A memory. A question: did this type of game ever happen in real life? A real match, players grouped by geography, not nationality—like golf’s Ryder Cup, but for football romantics.

I dug into the archives. The answer came quickly.

Yes.

The Europe XI is a real thing. What football historians call a “scratch team”—usually assembled for a special match: a testimonial, a charity event, or a symbolic celebration.

The first one dates back to 1938, when Europe XI faced England in London to mark the 75th anniversary of the English FA. England won 3–0. Over the decades, these games popped up sporadically. One notable example came in 1964, when the Europe XI faced Yugoslavia in Belgrade to raise funds for victims of the Skopje earthquake. Europe won 7–2, with Eusébio scoring four goals in a display of brilliance.

“

For one glorious evening, the greatest strike partnership that never truly existed… did.

A Dream Brought to Life

But it’s in 1997 that fantasy bleeds into reality.

To mark the draw of the upcoming 1998 FIFA World Cup, a special exhibition match was organised at the Stade Vélodrome in Marseille. For only the second time in history, Europe XI faced off against a World XI. The first time had been back in 1982 for a UNICEF charity match. This time, however, it was broadcast to the world as a spectacle—and, unknowingly, a moment of myth.

Because that night, for the first and only time, Ronaldo and Batistuta started together.

Not in a video game. Not in someone’s imagination. But on the pitch. In the flesh.

The Line-ups (a time capsule)

World XI: Songo’o; Hong Myung-bo, Javier Margas, Noureddine Naybet, David Nyathi; Marcelino Bernal, Hidetoshi Nakata, Adel Sellimi, Anthony de Ávila; Ronaldo, Gabriel Batistuta

Europe XI: Andreas Köpke; Heimo Pfeifenberger, Alessandro Costacurta, Fernando Hierro, Dominique Lemoine; Paul Ince, Marius Lăcătuș, Krasimir Balakov, Zinedine Zidane; Patrick Kluivert, Alen Bokšić

Just pause. Look at those names. Legends, icons, cult heroes—and two forces of nature up front for the Rest of the World.

A Symphony in Four Movements

Nine minutes in, Batistuta receives the ball near the halfway line and slides it across to Ronaldo on the right. The Brazilian bursts forward and unleashes a strike—just over the bar. A warning.

Ten minutes later, Ronaldo glides into the box from the left and hits a left-footed shot to the far post. 1–0.

In the 29th minute, it’s Ronaldo who turns provider, feeding Batistuta just outside the area. One touch. One bullet. 2–0.

Barely five minutes pass, and Ronaldo—surrounded by bodies—flicks a sublime scoop pass over the backline. Batigol, thundering in, meets it on the half-volley. 3–0.

By the 40th minute, Batistuta repays the favour once more—launching a long pass from deep midfield. Ronaldo darts between the defenders, outruns the onrushing Köpke and slots home. 4–0.

It was magic. Unreal. Unrepeatable.

The final score? 5–2 to the World XI. But the numbers didn’t matter.

What mattered was this: for one glorious evening, the greatest strike partnership that never truly existed… did.

The Duo That Could’ve Conquered the World

They never played together at club level. Never wore the same shirt outside that fleeting exhibition. But Ronaldo Nazário and Gabriel Batistuta remain, to this day, one of football’s greatest “what ifs”.

Imagine them at Barcelona. Or Inter. Or even Real Madrid. One all pace, improvisation and electric bursts; the other power, precision, and cold-blooded finishing. Brazil and Argentina, united—if only once.

Their careers were monumental in their own right. Ronaldo, the phenomenon. Batistuta, the lion. But together? They were art. They were poetry.

And for a few minutes in Marseille, they reminded the world what football could be.

Valdo – provisory title

He dribbled like a dancer, played with a smile, and made chaos look beautiful. A rebel with the ball, and a genius no system could ever hold down.

Italy’s 90’s Goalkeepers – provisory title

He dribbled like a dancer, played with a smile, and made chaos look beautiful. A rebel with the ball, and a genius no system could ever hold down.

Emilio Butragueño – provisory title

He dribbled like a dancer, played with a smile, and made chaos look beautiful. A rebel with the ball, and a genius no system could ever hold down.